News . 01-11-2023

Tea Sturua: “Viticulture is like walking on a tightrope”

Women winemakers in Georgia have long ceased to surprise anyone. The outdated misconception that women have no place in the cellar has been overcome. Georgian women winemakers have proven, through the quality of their wines, that they are capable of producing premium-class wines - a fact reflected in the growing interest of consumers.

Tea Sturua, founder of Patara Marani, is among those who have fully mastered the intricacies of viticulture and winemaking. She is a practical winemaker who has also embraced the philosophy and essence of natural wine. One can learn more from Tea than from many an ordinary winemaker. Her constant drive to deepen her knowledge - whether about vines or wine - and her ability to put that knowledge into practice are remarkable.

Tea does not shy away from contradictions or challenges. She readily admits to mistakes made early in her journey and is always willing to explain, teach, and share why, for example, it is often better to produce a smaller harvest if it means making a natural wine that, above all, brings joy to the winemaker.

- What does natural wine mean to you, and why did you choose this path?

- Natural wine is a free, naturally diverse creation born from the connection of soil, climate, micro environment, and people - terroir. I say “product,” but it is more than that: I know of no other plant in the natural world that, like the vine, tells its own story over the course of a year, ripens, and then returns all its trials and triumphs to the wine. Natural wine is alive - a bearer of emotion and feeling - sometimes imperfect, but always authentic, a storyteller of the harmonious coexistence of people and nature. Natural wine is truth and trust in a bottle.

- Why did you choose this philosophy?

- Because it is closest to my vision of who we are as humans, what role we play on Earth, why we have been gifted such diversity, and what responsibility that places upon us. The philosophy of natural viticulture and winemaking best expresses my values - freedom, honesty, trust, respect for individualism, and principle.

- What is the most important thing in the challenging process of caring for a vineyard, and what should a winegrower pay special attention to?

- In keeping with the philosophy I’ve just spoken about, I cannot give strict, prescriptive advice. I can only share my observations and feelings. A vineyard, for me, is not merely a plot of land where vines are planted - it is a living space that understands, feels, and shares its own “adventure,” and I am its listener. Yes, it is a demanding process. Every year brings new challenges; it is like walking on a tightrope. I don’t believe there is any fixed “recipe” or so called “standard guideline.”

- Viticulture and winemaking are not without challenges…

- Indeed. In this work, it can be difficult to resist many temptations, to stay true to your choices, and to fully trust nature - especially when winemaking is your livelihood. Still, there are general approaches: timely and correct pruning; maintaining grass and plant cover around the vineyard; promoting soil regeneration by avoiding rough or deep cultivation; composting; mulching; encouraging the presence of natural allies such as bees, birds, and pest controlling species; and ensuring good aeration. The frequency and depth of green operations depend on the climate in a given year. That means constant weather monitoring and, when needed, the timely application of treatments permitted in natural winemaking. Above all, it requires almost daily observation. For an organic winegrower, the most essential skill is the ability to observe and to respond promptly to any imbalance - with the lightest possible intervention.

- Tell us about your winery — when was it founded, what processes are you going through now, what vineyards do you own, and what types of wines do you produce?

- My story is rather unusual. We officially founded the winery only recently (2018–2019), yet my first steps in natural winemaking and viticulture go back to 2001–2005. There comes a moment when you pause, look back, and realize that taking that single, completely new and - at the time - untrodden path has forever bound your family to what you do today. It’s a long story - and worth telling - but for now I’ll just say that, since those early years, two people have stood behind me unfailingly: Gogi Tushmalishvili and Soliko Tsaishvili. Whenever I face a challenge, I often ask myself: What would Mr. Gogi advise? How would Soliko assess this?

In 2005, in a region entirely new to me (I am from Imereti) - Kakheti, in the Kardenakhi Akhoebi - I bought my first 0.5 hectare Saperavi vineyard. Soliko cared for it, and my husband often visited. At the time, I immersed myself in searching for and reading manuals and articles on natural viticulture and winemaking - not an easy task back then.

Today, in the same Akhoebi, I tend a newly planted (now four year old) 0.5 ha Saperavi vineyard and a 0.25 ha, eight year old Rkatsiteli. I also have a 0.5 ha, ten year old Rkatsiteli vineyard in the Tsarapi micro zone. I produce just two wines, both qvevri made, fully traditional and dry: Rkatsiteli and Saperavi.

Looking ahead, I plan to establish 1 ha of Rkatsiteli in Tsarapi and expand the cellar. I know firmly that I must resist the lure of larger harvests and greater volumes. We evaluate our physical and financial capacities carefully - how much vineyard we can truly care for under this philosophy. I keep learning, attending trainings, reading modern literature. The truth is, humanity has lost touch with nature; we no longer understand its language, and we must learn it again. This year, for the first time, I began using a mini weather station. Interpreting its data and translating it into action takes real knowledge and experience.

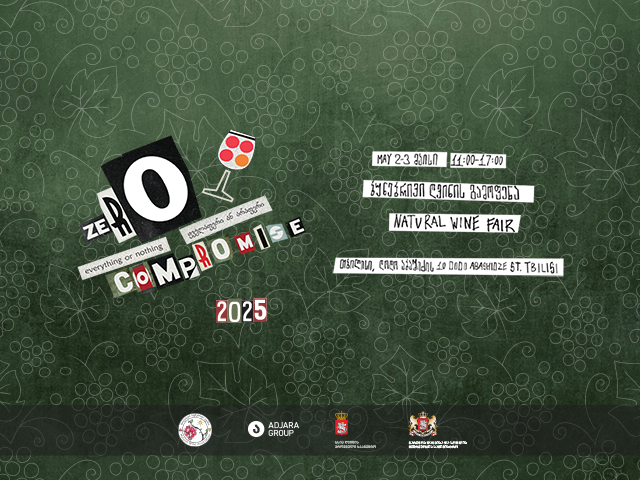

I am a member of the Natural Wine Association and take part in its festivals, tastings, and RAW WINE exhibitions. I look to the future, and today I still have mentors - Zura Mgvdliashvili and other members of the Association. With their support, I stand firmly by my principles. I know, I feel, that I am not alone; I grow and evolve, watching and listening to the ode of the vineyard and the wine.

- What advantages does qvevri wine have, and how do you see its potential for export abroad?

- I believe the qvevri remains a phenomenon not yet fully explained. We often say natural winemaking is difficult - producing qvevri wine is no less so. This unique vessel holds many secrets. Countless local and international researchers are trying to uncover them. Perspectives differ, but there is agreement on some key advantages:

- The vessel’s position - buried in the earth, it provides ideal, stable temperature conditions for natural fermentation and storage.

- The material - clay - its micropores ensure slow, gentle oxygenation (“the qvevri breathes”) so the wine doesn’t oxidize, allowing phenols and tannins to integrate calmly.

- The method - the ancient practice of fermenting and aging on skins and stems (chacha-klerti) for long macerations (about six months) gives wines distinctive structure and color, naturally filters them, and leaves them “alive,” rich in natural microflora for a long time, even in bottle.

And beyond all that, the qvevri is our tradition, our heritage - the original source of the world’s winemaking history.

From what I see in today’s global wine market, qvevri wine has strong export prospects. Over the past 10–15 years, demand has grown for small batch wines free from chemical processes and technological manipulation, wines offering new flavors, authenticity, life, an unfiltered, sulfur free profile, and the clearest possible expression of terroir. Qvevri wines embody tradition and a living connection to wine’s history, which in turn fosters a sense of “spontaneity” that emotionally links consumers to the vineyard, the land, and the people who bring these wines into being.

- If you were starting viticulture and winemaking now, would you follow the same path? Have you made any mistakes you wouldn’t repeat if you were beginning from scratch?

- I often reflect on this. I would choose the same path again. In natural viticulture and winemaking, I believe the difficulty, risk, and labor involved will only continue to grow, because we must coexist alongside growers with different values. That said, I would now meet these challenges with greater preparation and awareness.

Have I made mistakes - or do I still? Of course. There is still so much for me to learn. I remain, in many ways, far from nature; I still do not fully understand its language.

Levan Sebiskveradze